The Wealth Gap through Values

Asher Faamoe

Values can be defined as “the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something” (Lexico.). Looking at the issue of Wealth Gap through the lens of Values means that we are looking at what people value and how that plays into the change in the wealth gap. To begin examining the wealth gap it is good to look at where it began in America and that could be during the typographic age in America.

When colonists first settled in America, The Wealth Gap in America started to form instantly. During the Typographic age almost everyone was able to read and write and the entire country valued everyone’s ability to read and write. During the Typographic age in America “most people could read and did participate. To these people, reading was both their connection to and their model of the world” (Postman. P. 62). The people during this time valued the art of reading because it meant their connection to the world and it was one of the main forms of entertainment. However, since reading was valued so highly it questions what it meant to those who could not read. During the Typographic age “o attend school meant to learn how to read” but, that means that if people did not go to school they never learned to read and back then “ there did not exist such a thing as a ‘reading problem,’ except, of course, for those who could not attend school” (Postman. P. 61). What this meant is that the people who were unable to attend school never learned to read which separated them from the rest of the country. Getting to a deeper meaning however, if people did not attend school, it typically meant that they could not afford to attend school because of where they lived, whether they had the funds to attend school or not, or possibly due to how they were treated in society according to their race. Back in the typographic times people were essentially separated from the rest of the society if they couldn’t afford to attend school and learn to read. The Wealth Gap was not very large during this tome but, it began to expand as the country continued to grow.

Another example of how values play into the Wealth Gap in America can be seen when the Irish immigrated from Ireland to America. When the Irish population immigrated to America, they had a hard time trying to find jobs and they had to find some way for the American’s to hire them. What the Irish discovered is that they “competed against blacks for employment” so, “the Irish newcomers sought to become insiders, or American’s, by claiming their membership as whites” (Takaki. P. 143). The fact that the Irish had to turn to this method of getting jobs represents a few different things. In doing this the Irish showed where their values lay, their values lay due to their position within the Wealth Gap. They found themselves at the lower end of the Wealth Gap and they valued receiving money and living over morals. It is interesting seeing how they did this because it is interesting how the Irish immigrants had a shift in value due to their change in wealth. The Irish doing this also proved how hard it was (and is) to get a job if you were an immigrant or a person of color. It shows how the industrial companies value white American workers over the black population or immigrants.

This problem is also apparent today though, when interviewing our community partner, an economic teacher at Cascadia Lisa Citron, she said that ‘industrial racism has helped to create the wealth gap between races’ which is so significant in the Wealth Gap. The Wealth Gap has a to do with how employers value their employees and who they want to employ. Most employers, during most of the twentieth century, valued their white employees over any employees that were of color or immigrants. After years of employers favoring the white population it helped create this Wealth Gap where more people of color are at the bottom of the wealth gap and white people are at the top of the Wealth Gap.

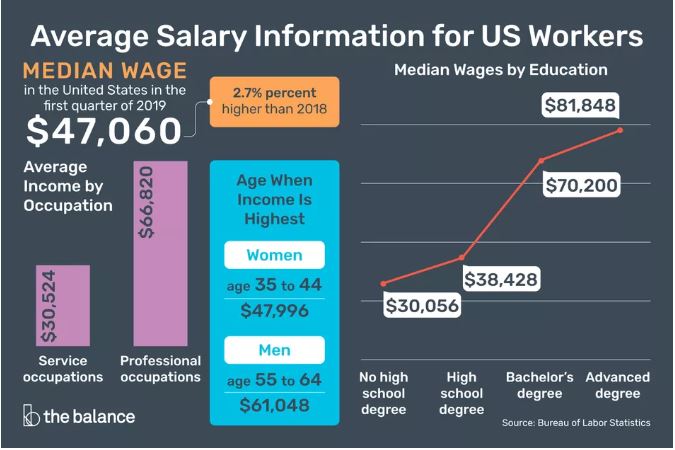

The Wealth Gap extends farther than just race when pertaining to jobs, it also depends on what jobs people are able to get. During our interview with our Community Partner, Citron also told us about how ‘people in less populated places will take whatever jobs are available to them’. The fact that people are just taking the jobs that are available to them in their home town shows a whole different way that people value jobs and the money they receive from said jobs. They may not care about the money and value the home that they have in that town, or they may value the culture around that job or whatever it may be, they value the job in their hometown. However, the job market and everyone’s values shifted and changed after the 2008 recession. During out interview, Citron also said that ‘the recession changed the job game because everyone started requiring degrees’. After the recession, the employers around the country started to value a degree much more because the job market became tougher and they had to narrow down the requirements in some way. The recession also made people value school much more and thus value education all around the board much more than before. Everybody around the country started to have a harder time getting jobs and it inflated the Wealth Gap in massive ways. It expanded the population of people at the lower end of the Wealth Gap while also boosting how high the rich end of the Wealth Gap can be. However, due to this change in values in employers, it changed the game of job hunting and created this pocket of jobs that people became stuck getting because of their level of employment. It changed the way people value school forever.

However, it is good to look away from just the job market in America and look at how the Wealth Gap is forming the values of parents and their children in school. In 2018 The New York Times published an article about how there is a digital gap between rich and poor kids. In this article Nellie Bowles talks about how kids that are attending private schools are beginning to become less attached to technology because the schools believe they should be teaching with less connections to the devices we have. at the same time, she talks about how children in lower income families are more connected to the devices and smartphones because the schools are finding that it is becoming easier and cheaper to teach with these devices in school. The reason this form of diversity is important is because it shows where some parents values stand depending on their position within the Wealth Gap. Parents in the middle and lower class sending their children to public schools may not want “their kid to be the lone weird one without a phone” and purchase a smart phone for them early in their childhood (Bowles. 2018). What this does is it gives kids going to these public schools an addiction to the smart phones they have grown up on because “Lower-income teenagers spend an average of eight hours and seven minutes a day using screens for entertainment, while higher income peers spend five hours and 42 minutes” (Bowles. 2018). What all of this means is that the values of the lower and middle class don’t match the values of those in the upper class (AKA the other side of the Wealth Gap). The “children of poorer and middle-class parents [being] raised by screens” have more value in their smart phones and devices while the children in the upper class have values that extend farther than the simple device (Bowles. 2018). The main point of this example of kids having different addictions to screens pertains to how depending on what side of the Wealth Gap you are on forms the different types of values people have as individuals.

References

Value: Definition of Value by Lexico. (n.d.). Oxford. Retrieved from; https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/value

Postman, N. (2007). Amusing ourselves to death: public discourse in the age of show business. London: Methuen.

Takaki, R. T. (2008). A different mirror: a history of multicultural America. New York: Back Bay Books.

Citron, L. (2020, February 12). [Videoconference interview by A. Knoll, A. Faamoe, & I. Mankis].

Bowles, Nellie. (2018, October 26). The New York Times. The Digital Gap Between Rich and Poor Kids Is Not What We Expected. Retrieved from; https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/26/style/digital-divide-screens-schools.html